Q: Can the 10.5% Net CFC Tested Income (NCTI) regime really beat an S-Corp for a small-business owner?

A: Only in very specific circumstances. Under the Net CFC Tested Income (NCTI – formerly GILTI), the structure can win if you’re a high-earning US expat who (1) routes profits through a US C-Corp that owns a bona fide foreign subsidiary, (2) keeps all revenue-generating activity outside the US (no ECI, employees, or dependent agents), (3) pays yourself a foreign salary, and (4) is willing to handle ongoing Form 5471, CFC, and foreign-bank compliance for years before touching the cash. Miss any of those hoops and a straight S-Corp – or possibly a hybrid S-Corp/C-Corp setup – almost always produces a lower effective tax rate with less complexity.

TL;DR

- Global Intangible Low-Taxed Income (GILTI) has been updated to Net CFC Tested Income (NCTI) as part of the OBBBA legislation.

- 10.5% rate isn’t magic. Compliance costs, Section 250 deduction change (12.6% in 2026), and dividend tax can erase the headline savings.

- Must use a two-tier structure. A US C-Corp owns the CFC – direct individual ownership won’t qualify for the Section 250 deduction.

- Live abroad + zero ECI. Any US office, employee, or dependent agent creates “effectively connected income” and kills the benefit.

- It has to be a business, not just you. Pure personal-service income fails the assignment-of-income test.

- S-Corp is still better for most US owners. Once payroll tax and dividend tax are factored in, S-Corp wins at typical profit levels.

- Hybrid S-Corp/C-Corp NCTI can beat solo NCTI at ≈ $500k+ profit if you can leave earnings parked in the C-Corp for years – watch AET/PHC traps.

In a previous series of articles, we got into the math on C-Corps and how – for the vast majority of taxpayers – they are a bad choice for their small business. We noted how they can be used strategically in conjunction with an S-Corp, although even that requires some specific criteria be met.

There is one other exception where a C-Corp may actually be the best choice for your company – although the criteria for meeting it are even more specific. This is if you qualify for the Net CFC Tested Income (NCTI). Prior to the OBBBA being passed, this was known as GILTI.

Instead of the typical 21% corporate tax rate, qualifying NCTI income is subject to a reduced effective rate of 10.5% through 2025, increasing to 12.6% starting in 2026, due to changes in the Section 250 deduction. (Note: scheduled the 37.5% deduction/13.125% rate was scrapped under the OBBBA. The 40% deduction/12.6% are now permanent).

That sounds great – on the surface. Which is why many tax advisors stop right there. “Your previous CPA had you taxed as an S-Corp? That means you were paying 37% instead of 10.5%. What an IDIOT!”

The problem – just like with the normal C-Corp vs. S-Corp discussion – is that they stop right there. The NCTI setup can be a powerful tool in the right circumstances, but it’s not a fit for everyone.

What Is NCTI and Why Does It Exist?

The NCTI rules were introduced as part of the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) to discourage US companies from moving profits to offshore tax havens. Rather than try to tax every dollar earned overseas under traditional worldwide tax rules, Congress implemented NCTI as a kind of “minimum tax” on foreign profits. The goal was to keep multinational companies from parking earnings in low-tax or no-tax countries without penalizing legitimate international operations.

Despite its old name (“Global Intangible Low-Taxed Income” or GILTI), it isn’t limited to intangible income like patents or software. That may be why it was renamed to Net CFC Tested Income (NCTI) when the OBBBA passed. In practice, it captures nearly all foreign income earned by a “controlled foreign corporation” (CFC) – especially when that income isn’t being taxed much (or at all) in the foreign country. To offset this inclusion, qualifying US C-Corporations get a big break: they’re allowed a deduction under Section 250 that can cut the effective tax rate on this income down to as low as 10.5%.

How the NCTI Structure Actually Works

So how does the NCTI setup work?

Note: I want to qualify these next few sections by noting two important things from the outset:

- This is a complex tax structure. Setting up these structures in a compliant way that ensures you get all of the tax benefits is complicated and is not a DIY project. It should only be done by a specialized tax attorney.

- These sections are kind of long given the complexity (and niche nature) of the topic, so I don’t want that to be confused as this being the end-all analysis of the subject. This discussion is not intended to be all-encompassing, but more to give a broad- strokes overview of the factors at play. If you cannot meet the criteria in this article, then you won’t qualify for NCTI. But that doesn’t mean there aren’t other nuances in your specific situation that could make the structure unworkable, even if you technically check all the boxes.

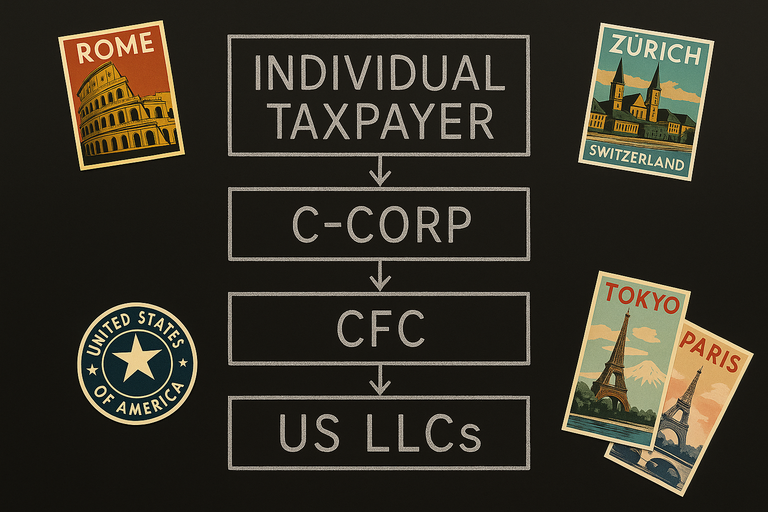

In order to qualify, a US C-Corporation must own at least 10% of a controlled foreign corporation (CFC). Individuals owning the CFC directly cannot qualify for the NCTI treatment. Some structures then have the CFC owning US LLCs for convenience (i.e., banking, payment processing). While this is acceptable, it does introduce some potential risk of the foreign entity being considered engaged in a US trade or business – and thus losing NCTI eligibility. This should only be done with careful legal review by an attorney.

Structurally, the most common setup you will see is:

- A US C-Corp 100% owned by a US citizen/taxpayer

- The US C-Corp 100% owning the CFC

- The CFC 100% owning US LLCs

Even though the LLCs are US entities, because they are owned by the CFC which is then owned by the C-Corp they can claim the 40% §250 deduction, yielding a 12.6% federal rate for fiscal years beginning after 2025 (10.5% before then).

The Catch: Why Most People Don’t Qualify

At this point, a lot of people are thinking, “Okay, I just need to funnel my business through a foreign corporation. Easy enough. A bit of a hassle, but worth it to slash my tax bill.”

Unfortunately, the Byzantine corporate structure is the easiest criteria to meet.

The next requirement is that you need to be living abroad. There’s no official rule that says you must live abroad to qualify for NCTI treatment. But in practice, if you’re living in the US and actively managing the business, you’re almost certainly creating what’s called “effectively connected income” (ECI), which disqualifies the income from being taxed under the favorable NCTI tax treatment. That’s why this planning almost exclusively works for expats and digital nomads who operate entirely outside US borders.

This unofficial “requirement” knocks out the vast majority of business owners. You can’t just be a US resident with a foreign shell company and expect to get NCTI treatment.

But that’s just the first hurdle. The other one that gets commonly ignored is that “effectively connected income” (ECI) to the US. Even if you:

- Live overseas

- Funnel your business through a NCTI -compliant tax structure

None of that matters if it can be shown you have ECI. Remember, the entire intent behind this structure is to give more favorable tax treatment to foreign-earned income.

So how do they define ECI? Effectively connected income refers to income that is tied to business operations taking place within the United States. If the IRS determines that your foreign business has ECI, then it’s treated as if you’re running a US business – and the reduced NCTI tax rate goes out the window.

As outlined in IRC §864(c), income is considered “effectively connected” with a US trade or business if it’s generated by activities like having employees or agents in the US, maintaining a fixed place of business, or negotiating and signing contracts through representatives located here.

The “Dependent Agent” Trap That Can Blow Up Your NCTI Plan

The term my friend and tax attorney Stewart Patton uses is “ETBUS” or “engaged in trade or business within the US” and one of the main criteria for that is having what is called a “dependent agent”.

What is a dependent agent?

A dependent agent is someone in the US who regularly acts on behalf of your foreign company and has (and habitually exercises) the authority to make deals or sign contracts that bind the company. This includes agents who regularly negotiate or finalize deals in the US on behalf of the foreign business. Even if the foreign business is owned by a US expat and appears fully offshore, the presence of such an agent can create what’s known as a “permanent establishment” – once again disqualifying you from NCTI tax benefits.

In contrast, independent agents – like brokers or commission-based agents operating in the ordinary course of their own businesses – typically do not create this risk unless they act almost exclusively for one client or are economically dependent on that foreign enterprise.

As a rough analogy, you can think of dependent agents as employees and independent agents as contractors. Employees represent your business. Contractors run their own businesses and provide services to many clients – including you. The IRS is looking at how these agents function in practice, not what label you slap on their tax forms.

The focus of the article is for non-US Amazon sellers, but Stewart has an excellent article that discusses some of these issues.

Note: just paying everyone via a 1099 rather than a W-2 does not magically fix this issue. The IRS looks at how the agents are actually operating, not just how you classify them on paper.

If you have a US-based employee or dependent agent acting on behalf of your foreign company, the IRS can treat the income as ECI. That means it’s taxed under regular US corporate rules – not as foreign income – and you lose the NCTI deduction entirely.

Not All Work Qualifies: Business vs. Profession

Let’s say you pass all the other hurdles: you live abroad, your company has no US office, no dependent agents.

There’s still one more hurdle that doesn’t get talked about enough: Are you actually running a business – or are you just practicing a profession?

That distinction matters. If you are practicing a profession, the NCTI structure likely doesn’t work at all.

Why?

Because if all the income is generated by your own labor – coaching, consulting, freelance work, or anything else where you are the product – the IRS will likely treat that income as earned by you, not the entity. And if the entity isn’t truly earning the income, the entire strategy collapses. Because when the IRS sees through that, the tax deferral doesn’t just weaken – it disappears.

In several areas of tax law – including Subpart F, the foreign earned income exclusion, and even how income is sourced – the IRS consistently treats personal services differently from income earned by a broader, self-sustaining business. They’ve enforced that line repeatedly through what’s known as the “assignment of income” doctrine, established in the Supreme Court case Lucas v. Earl. The Court held that a person who earns income through their labor cannot assign that income to another party – even a company they wholly own – just to reduce taxes. As the Court put it: “The fruit cannot be attributed to a different tree from that on which it grew.”

Here’s the basic rule of thumb:

- Profession: You are the product. You stop working, the money stops.

- Business: There’s infrastructure, a team, deliverables, or systems. Value continues even if you step away.

NCTI deferral relies on the idea that the entity – not the individual – is earning the income. That argument breaks down if the entity is just a shell for your own professional services. So if the income ultimately traces back to your personal labor – not a business with its own value-generating infrastructure – the NCTI structure likely won’t stand up to IRS scrutiny.

The Compliance Minefield Most CPAs Ignore

Unfortunately, the majority of people pitching the NCTI setup basically skip…all of this. Not only do they not discuss any of the downsides inherent to all C-Corps (double taxation, loss of QBI, etc.), but they will be astonishingly sloppy with the compliance side.

We have spoken with people who had moved back to the US, worked actively in their businesses, and even had employees and physical locations in the US and their CPAs were still filing them under the NCTI setup. Occasionally this came from CPAs who branded themselves as “expat” experts.

It’s hard to understand how there can be that level of negligence – but unfortunately, it happens. If you’re reading this, take it as a serious note of caution: you must understand this structure yourself. The IRS doesn’t care if your CPA misunderstood the rules – you’ll still be the one on the hook if the structure is deemed noncompliant.

S-Corp vs. NCTI: Side-By-Side Tax Math

Alright, now that we have three pages of baseline explanation out of the way, what does the math actually look like? Assuming you do qualify, does this setup make sense for you?

Since – in practice – this setup only works for expats, we’re going to apply the following assumptions to the scenarios below:

- Salary equal to FEIE: The taxpayer takes a salary at least equal to the full Foreign Earned Income Exclusion (FEIE) amount – $130,000 for the 2025 tax year.

- For S-Corps, the salary may be set higher to optimize for the Qualified Business Income (QBI) deduction.

- No foreign housing exclusion assumed: We’re not including the foreign housing exclusion, since its benefit varies widely depending on where the taxpayer lives.

- Payroll tax treatment:

- For S-Corps: salary is paid via a US company and is subject to US payroll taxes.

- For NCTI: salary is paid from the foreign CFC and assumed not subject to US payroll taxes.

- No wages scenario: We also model a case where no wages are paid (i.e., the taxpayer does not qualify for the FEIE).

- This is a suboptimal structure, but it is technically possible under NCTI.

- We are not factoring in any foreign tax credits. What you pay, how much of it qualifies, and whether it can be credited against US tax depends heavily on the country where you live (or where your CFC is based) and other factors.

- Other assumptions:

- Single taxpayer

- No other sources of income

- Earnings are fully and immediately distributed

We’ll run this at three income levels: $200k, $500k, and $1 million.

| Income Level | Entity Type | Income Taxes | Distribution Taxes | Social Security / Medicare | Total Taxes Paid |

| $200,000 | S-Corp | $11,000 | $0 | $20,000 | $31,000 |

| NCTI (wages) | $7,000 | $8,000 | $0 | $15,000 | |

| NCTI (no wages) | $21,000 | $36,000 | $0 | $57,000 | |

| $500,000 | S-Corp | $92,000 | $0 | $23,000 | $115,000 |

| NCTI (wages) | $39,000 | $65,000 | $0 | $104,000 | |

| NCTI (no wages) | $53,000 | $77,000 | $0 | $130,000 | |

| $1,000,000 | S-Corp | $247,000 | $0 | $31,000 | $278,000 |

| NCTI (wages) | $91,000 | $182,000 | $0 | $273,000 | |

| NCTI (no wages) | $105,000 | $197,000 | $0 | $302,000 |

Note: The higher distribution taxes under the “no wages” column reflect full double taxation at qualified dividend rates, since no salary was taken and all profits are distributed post-corporate tax.

The math on this looks a lot better than it would with a traditional C-Corp. They’re competitive or favorable in all of these scenarios, but it’s not nearly as good as the 10.5% rate would make you think.

When the rate increases to 12.6% next year, the math gets even worse:

| Income Level | Entity Type | Income Taxes | Distribution Taxes | Social Security / Medicare | Total Taxes Paid |

| $200,000 | S-Corp | $11,000 | $0 | $20,000 | $31,000 |

| NCTI (wages) | $9,000 | $8,000 | $0 | $17,000 | |

| NCTI (no wages) | $25,000 | $36,000 | $0 | $61,000 | |

| $500,000 | S-Corp | $92,000 | $0 | $23,000 | $115,000 |

| NCTI (wages) | $47,000 | $65,000 | $0 | $112,000 | |

| NCTI (no wages) | $63,000 | $77,000 | $0 | $140,000 | |

| $1,000,000 | S-Corp | $247,000 | $0 | $31,000 | $278,000 |

| NCTI (wages) | $110,000 | $182,000 | $0 | $292,000 | |

| NCTI (no wages) | $126,000 | $197,000 | $0 | $323,000 |

Even in the scenarios where you are paying less in taxes, those savings are mostly coming because you are not paying into Social Security and Medicare. We’ve noted this many times in the past, but while the ultimate benefit we will receive from Social Security is unclear, we will receive something. All other things being equal, it’s better to contribute to Social Security vs. just paying income tax.

When NCTI Actually Makes Sense

That’s not to say there is no situation where the NCTI setup makes sense. In the scenario of $200k income, even when the rate goes up to 12.6% you’re saving $14k – which is nearly half of what the S-Corp liability is. Admittedly, that is done at the cost of Social Security contributions, but that $14k savings can be used to reinvest in your business or find other investments to indirectly fund your retirement.

The main situation where this can be helpful is the same as the one we outlined in our hybrid S-Corp and C-Corp article. It works if you:

- Are a very high earner

- Have multiple companies (or can split your existing company into multiple companies)

- Do not need to distribute the C-Corp funds to yourself for a long period of time

If you meet those criteria, it can be a powerful strategy.

Let’s say you earned $1 million but it was split $500k into an S-Corp and $500k into a C-Corp. How does this hybrid strategy look compared to the others?

| Income Level | Entity Type | Income Taxes | Distribution Taxes | Social Security / Medicare | Total Taxes Paid |

| $1,000,000 | S-Corp | $247,000 | $0 | $31,000 | $277,000 |

| NCTI (wages) | $110,000 | $182,000 | $0 | $292,000 | |

| NCTI (no wages) | $126,000 | $197,000 | $0 | $323,000 | |

| Hybrid | $155,000 | $77,000 | $23,000 | $255,000 |

That’s $20,000 in tax savings compared to the standard S-Corp route – even after you take money out. In the meantime, you have access to nearly $100,000 more in retained capital to reinvest in your business or stash away for the future. That kind of flexibility can compound quickly.

Watch Out for the Accumulated Earnings Tax and Personal Holding Company Rules

If you are considering utilizing that hybrid NCTI structure, you need to be keenly aware of the downsides. We noted all of them in that original hybrid S-Corp and C-Corp article, but one issue deserves a special spotlight. We’re quoting that section here directly for emphasis:

“Before we get into the other downsides, this one deserves its own spotlight.

If you try to let profits pile up inside a C‑Corp without taking distributions – or without a clear, documented plan for reinvesting those earnings – you risk triggering the Accumulated Earnings Tax (AET). It’s a 20% penalty the IRS applies when they think you’re stockpiling cash to avoid personal-level taxes on dividends.

The safe harbor lets you retain up to $250,000 in the company ($150,000 for service businesses) without a problem. But beyond that, the IRS expects a legitimate business reason for why the money is still there. Not just “I might need it someday,” but actual capital needs: equipment, growth, hiring, expansion, R&D, etc. If they don’t buy your explanation, they can assess the AET on top of the regular corporate tax you’ve already paid.

It’s not always “actively” enforced (i.e. just by passing the $150k or $250k threshold the IRS is not going to automatically come knocking on your door). And this is another reason that gurus will pitch C-Corps so aggressively: plenty of entities that technically violated AET rules haven’t been audited yet. But if the IRS audits and sees excessive retained earnings with no real plan behind them, this could undo much (or all) of the tax benefit you were counting on.

In a similar vein, the Personal Holding Company (PHC) rules impose a 20% penalty tax on closely held C-Corps that generate most of their income from passive sources – like interest, dividends, royalties, or rents – and are owned by five or fewer individuals. The IRS uses this rule to prevent corporations from being used as investment vehicles to shelter personal income. If your hybrid structure includes passive income streams, or you’re holding intellectual property or investments inside the C-Corp, you’ll want to monitor PHC exposure closely. Distributing sufficient dividends or maintaining active business operations can help avoid this trap. But then again, if you’re regularly having to distribute the earnings the benefit of this tax structure disappears.

So if your whole plan relies on deferring income tax by leaving money in the C Corp indefinitely, you need to be thinking about AET and PHC from day one. They’re not always enforced, but when they are, they can completely undermine the strategy.”

Final Thoughts: Is NCTI Right for You?

The NCTI setup can be a powerful tool, but only for people in very specific and often uncommon circumstances. The parameters required for it are strict and even for those who qualify, oftentimes an S-Corp or a hybrid S-Corp/NCTI setup is going to be the best option.

Even when the numbers work, this isn’t a set-it-and-forget-it structure. You’ll need to manage things like Form 5471 filings, CFC compliance, foreign bank disclosures, and regular legal reviews to stay on the right side of the IRS.

There are easier, simpler structures out there. For the majority of taxpayers, those simpler structures are also more advantageous from a tax-perspective. But if you’re a high earner living abroad, have a long runway before you need to access funds, and are comfortable with ongoing legal and tax complexity – this may be one of the few places where a C-Corp (or a C-Corp alongside an S-Corp) can outperform an S-Corp.

FAQ

What is NCTI?

Net CFC Tested Income – formerly known as Global Intangible Low-Taxed Income or GILTI – is essentially a US minimum tax on foreign profits earned by a controlled foreign corporation (CFC). A US C-Corp gets a Section 250 deduction that cuts the effective federal rate to 10.5% (12.6% after 2025).

Who actually qualifies?

US citizens living abroad whose US C-Corp owns ≥10% of a CFC, with no US office, employees or dependent agents—and whose income comes from a bona fide business, not pure personal services.

What disqualifies me?

• US residence or frequent US work trips

• US employees or dependent agents signing deals

• Personal-service income where you are the product

• C-Corp stockpiling cash beyond AET limits without a documented plan.

Is skipping payroll tax part of the benefit?

Yes – but avoiding Social Security and Medicare reduces future benefits, so it’s a trade-off, not a free win.

When might a hybrid S-Corp/C-Corp beat pure NCTI?

When the business consistently earns more than you need to live on abroad, allowing you to:

1️⃣ Pay yourself a market-rate S-Corp salary that soaks up the FEIE and any foreign tax credits, then

2️⃣ Park surplus profits in a C-Corp long enough for the deferral to outweigh future dividend tax.

The break-even point depends on profit margin, reinvestment horizon, local tax rates and Section 250’s phase-down – not on a single dollar threshold.

Any accounting, business, or tax advice contained in this communication, including attachments and enclosures, is not intended as a thorough, in-depth analysis of specific issues, nor a substitute for a formal opinion, nor is it sufficient to avoid tax-related penalties.